The 2013 southern Alberta floods did more to Calgary than damage houses and severely interrupt lives; the floods unearthed and highlighted a problem that has caused concern, and worse, for decades. In July, two unexploded military shells were found on the shores of the Elbow river in the Weaselhead area, exposing a legacy of unexploded ordnances (UXO) that lie just beneath the surface of a portion of southwest Calgary, including the potential route of the southwest ring road.

(Image of shell found in the Weaselhead area, July 2 2013. Courtesy Mark Langenbacher)

The Military and the Tsuu T’ina Reserve

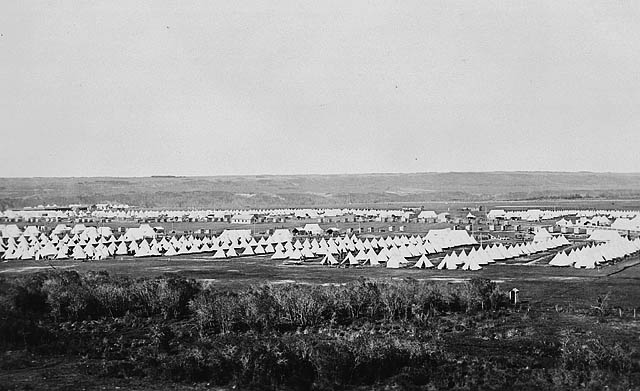

In 1910 the Canadian Military officially used a portion of the Tsuu T’ina reserve for a few days of summer maneuvers for the first time, and in 1915 a permanent camp was established on the north east corner of the reserve, which would soon become the largest military camp in western Canada for training soldiers for World War I. This triangular piece of land, then called Sarcee Camp and later known as Sarcee Barracks, Harvey Barracks and ‘The 940’, is defined by Glenmore Trail to the north, 37th street SW to the east and the Elbow river to the southwest. The area was leased until 1952 when the Department of National Defence purchased the land outright from the Nation. (See the map below). For more information about this land, click here.

(Sarcee Camp, Military District No. 13 1915. Library and Archives Canada / PA-147485)

In addition to the original camp, the Military leased an additional 11,050 acres of land (later, 11,800 acres) to the south of the Elbow river in 1924 in order to substantially increase the type of training that could be undertaken at Sarcee Camp. Though small-arms training was still carried out at firing ranges at Sarcee Camp, the new Sarcee artillery range would prove ideal for larger-scale training. The original rent of five cents per acre resulted in an annual payment of $552.50.

In 1931 the City of Calgary purchased the Weaselhead area, which included portions of both the Sarcee Camp and the Sarcee Artillery Range, and the area was protected as part of the Glenmore reservoir. Though the bridge and road through the Weaselhead remained the primary connector between the two military areas until the 1950s, and continued to be used for maneuvers by the military, live fire or artillery training is not known to have officially been undertaken in this area following its purchase by the City.

Between the 1920s and the 1990s the two parcels of land were used for a wide range of weapons training, with the larger-scale and more destructive exercises taking place on the artillery range.

By Land, Air and Sea

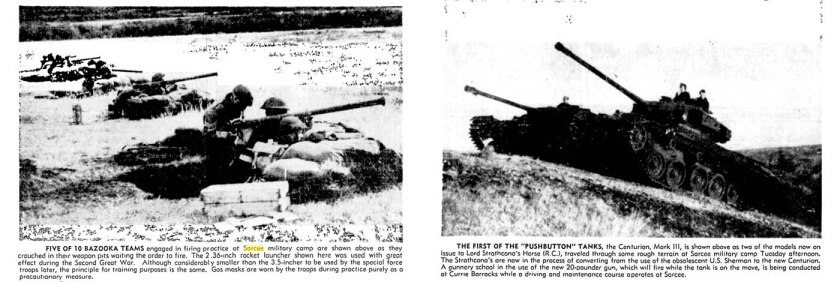

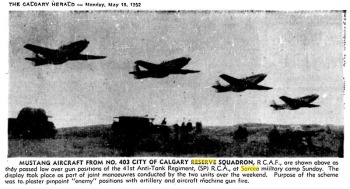

Throughout its existence, the Sarcee artillery range was used for tank maneuvers and firing practice, for personal arms like bazooka, grenade and small arms firing, for anti-aircraft practice and for artillery firing including howitzer and field gun, mortar and rocket practice. In addition, experience in how to deal with chemical attacks was afforded to soldiers by being exposed to tear gas, both with and without their gas masks.

Large-scale ‘war games’, often enacted with forces of over 1000 men, were held on the range involving soldier, tank and artillery regiments attacking and defending critical points of terrain. These exercises often included the air force, who supplied support aircraft from the nearby RCAF Station Calgary (later Lincoln Park) and used the range for bombing practice. Even the Navy was involved in training exercises in the area; during World War II the Glenmore Reservoir hosted naval maneuvers which included water-based attack and defence training, as well as landing exercises at the Weaselhead Bridge.

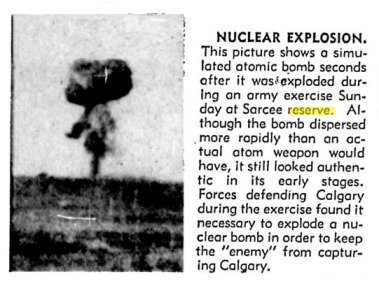

Traditional ‘war games’ were held on the artillery range for decades and new elements were added and updated in response to real-world military developments. In 1957 the Military wrapped up a 2-day large-scale exercise on the Sarcee artillery range with a new element; a mock atomic bomb explosion. The blast (documented below) was the result of an explosive device reportedly containing “jellified gasoline, acid and 40 to 50 pounds of TNT” being detonated on the reserve. The explosion’s fireball and mushroom cloud rose 500 feet in the air and was visible from central Calgary. The use of a mock atomic blast on the Tsuu T’ina reserve, which resulted in a 12 foot-wide crater, was not to be a unique event; the military also kicked off it’s 1963-1964 season of training with another simulated nuclear explosion.

For more than 50 years the military had used the artillery range for live-fire training purposes, and this intensive and destructive use of the land meant that a new danger would soon present itself.

Unexploded Ordnances: Injuries and Fatalities

With decades of use and perhaps millions of munitions fired on the land, the problem of unexploded ordnances was literally lying just below the surface. Incidents taking place on the reserve and within the City of Calgary involving the injury of civilians, though rare, were serious and becoming a concern.

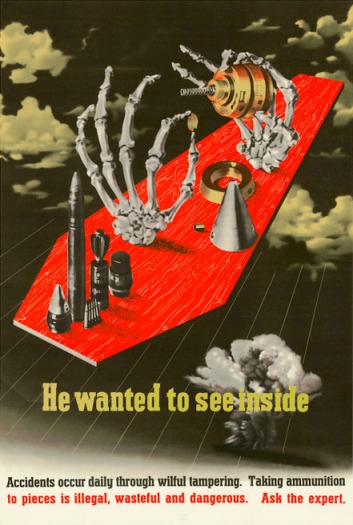

In December of 1944 several children were injured when they found an unexploded mortar in the Weaselhead area. 16 year-old Fred McCall, son of Captain Fred McCall after whom McCall Lake and McCall Field in Calgary were named, suffered from a chest wound and a lacerated leg after attempting to dispose of the shell. A friend was treated for shrapnel injuries and two others escaped unharmed when the boys burned the shell in a camp fire in an attempt to remove the danger the shell presented to other members of the public. The next year an 11-year-old boy lost several fingers and a thumb, and suffered from injuries to the face and legs after playing with live grenades at Sarcee Camp, three of which detonated at his feet. Following this incident, the Military began to place warning posters (specifically the one pictured below) in Calgary schools to warn children of the dangers of unexploded ordnances.

These incidents were not limited to children or to locations within the City. In 1953 Mrs. Clara Big Plume and her daughter and two grandchildren were seriously injured and ended up in hospital after the detonation of a found shell. Samuel, one of Mrs. Big Plume’s grandsons who was 11 at the time, had picked up a live anti-tank ‘piat’ shell, and in a 2000 interview he stated that he still carries 11 pieces of shrapnel in his body.

The severity of incidents came to a head in the winter of 1953 with the deaths of several soldiers. In February of that year, an apparent ‘dud’ bazooka shell was discovered on a shooting range at Camp Sarcee by a group of new recruits of the 2nd battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. While the shell was being examined, it exploded, killing three men and injuring four more.

Though the presence of unexploded ordnance was already concerning to both the Military and the Nation, events were in motion that would bring this issue to the fore. Changing circumstances regarding the use of the land meant that unexploded ordnance would soon play an increasingly central role in the relationship between the Department of National Defence and the Tsuu T’ina.

End of an Era

In the mid-1970s the Tsuu T’ina wanted to regain ownership of the 940 acre parcel of land that was sold in 1952 for the Sarcee Barracks, and also sought to increase the rent on the artillery range lease. The Nation stated that they were willing to use the return of the barracks land as partial payment of the rent for the artillery range. This proposal was rejected by the Department of National Defence, and coupled with stalled negotiations over the rental price, the lease for the artillery range was allowed to expire in 1981; for the first time in 57 years, the artillery range would no longer be available to the Military.

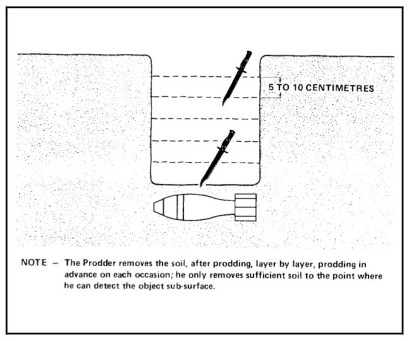

As part of the decommissioning process for handing the land back to the Tsuu T’ina, a land clearance program was instigated by the Military. In 1981 two operations, ‘Operation Bilbo’ and ‘Operation Roulette’, which was conducted over 16 days with over 1000 soldiers sweeping portions of the land with metal detectors, were undertaken. The operations were set to first clear the surface of the land of any exposeds munitions, and then sweep for ordnances buried to a depth equal to the effective range of the MINEX 4C mine detector, which was between 30cm and 45cm. Areas with positive readings were ‘prodded’ to identify the location and nature of the subsurface find (see below) before being marked for clearance.

(Diagram from ‘Operational Training, Volume 3, Part Three, Range Clearance Handbook’. Department of National Defence, Canada. 1982)

Despite the work involved and the recovery of thousands of individual munitions in 1981 (including unconfirmed reports of Operation Bilbo personnel finding an old tank that was reportedly lost during maneuvers in the 1950s), the military indicated that the clean-up would not be exhaustive. Deputy Commander of Canadian Forces Base Calgary, Colonel Dean Wellsman, stated at the time “We quite frankly don’t know what’s out there… There was a rather haphazard arrangement in the use of land during the war when the priority wasn’t on paper work. Records weren’t kept the same way they are now.”

Colonel Wellsman stated even more directly “We can never guarantee the land will be safe”. It was reportedly stated that while the Canadian government would still be liable for any injury resulting from an unexploded ordnance, it wouldn’t be because the band wasn’t warned.

Litigation, Agreements and Settlements in the 1980s

In 1982, following the return of artillery range, the nation filed suit against the Canadian government to both reclaim the barracks lands and to ensure proper clearance of the artillery range; the apparent inadequacy of the land clearance was a prime concern of the Nation.

Though the artillery range had been returned to the Nation, it would not be out of action for very long. In 1985 the Tsuu T’ina and the Military were back at the negotiating table, and soon signed an agreement over use of the artillery range. This ‘Sarcee Training Area Settlement Agreement’ established a lease on a portion of the original artillery range, provided compensation for previous land contamination and agreed to further clearance of the artillery range site.

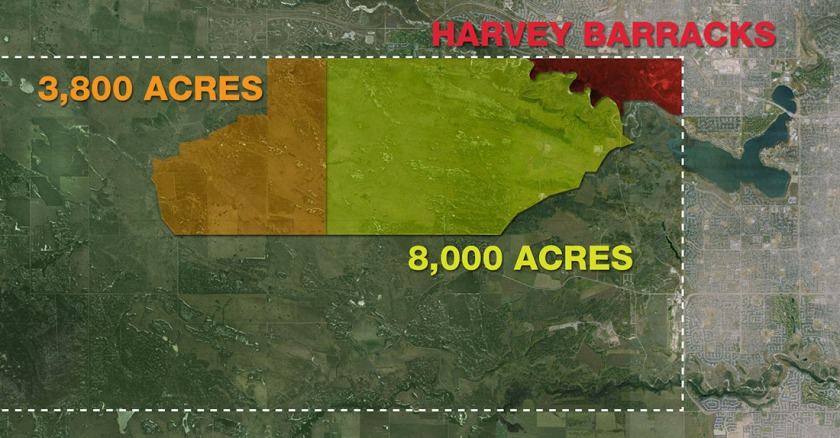

Whereas the previous artillery range lease totalled 11,800 acres, the new 20-year lease was for an 8,000 acre site, with the remaining 3,800 acres to be cleared and returned to the Nation (see map above). This smaller portion of land was set to be cleared no later than the end of 1990. Though the remaining 8,000 acres was still to be used for military training, it was agreed that this land was also to be cleared once the lease was over and operations on the land ceased. In an attempt to stop further contamination of the artillery range, the new lease also prohibited the use of munitions that were likely to result in unexploded ordnances. The use of “any explosives, or munitions containing explosives, grenades, or any air to ground ordnance whether inter or explosive” was prohibited going forward, though small-arms ammunition and small amounts of plastic explosives were allowed under a later amendment to the agreement.

The compensation for the previous contamination of the artillery range totalled $11.5 million and served to settle the artillery range portion of the 1982 lawsuit. All claims against the Crown by the Nation over the use and operation of the artillery range was released upon the approval of the agreement by a referendum of Nation members. The agreement also required the Tsuu T’ina to hire an expert in ordnance removal to oversee and advise the Nation on the clearance efforts by the military.

Direct Action

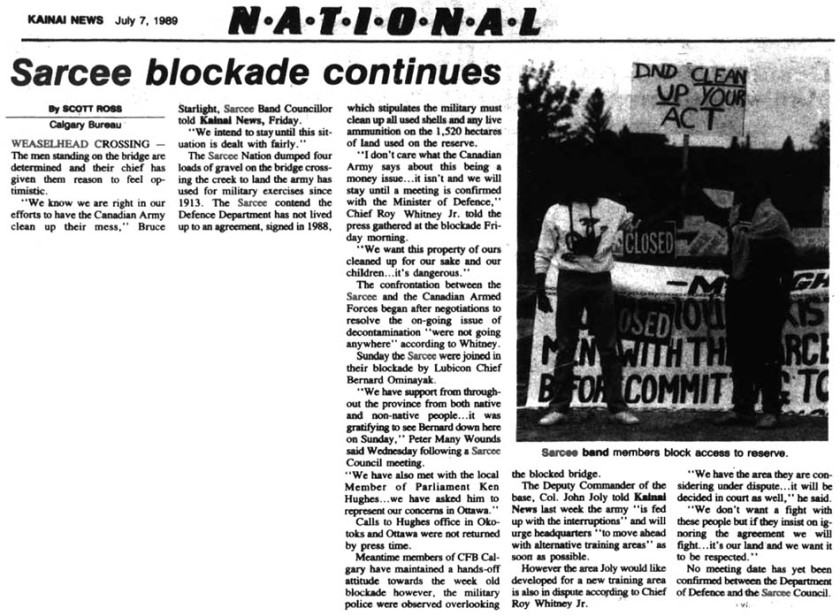

Despite having an agreement in place to clear the unused portion of the artillery range there was growing concern that the clearance was not adequate. After pressing for further clearance of lands within the artillery range, the Tsuu T’ina decided to take a more direct approach to ensuring that the agreement was adhered to. On June 30 1989, members of the Nation dumped four loads of gravel on the private Weaselhead Bridge that connected the Harvey Barracks with the artillery range over the Elbow river, effectively denying use of the artillery range to the military.

The Nation was protesting what they considered to be inadequate clearance of the artillery range and demanded that the terms of the 1985 lease agreement be respected. Captain Brian Lloyd, a retired British Army bomb disposal expert hired by the Tsuu T’ina, stated at the outset of the protest that despite early clearance efforts, since 1981 over 1300 pieces of ordnance had been recovered, 80 of which were live.

Military representatives disagreed with the Nation’s assessment of the situation, insisting that the $11.5 million paid to the Nation in 1985 was to compensate the Nation for land that could never be fully cleared. The difference of opinion seems to revolve around the different interpretations of ‘clean’; the Military wanted to adhere to the clearance process as outlined in the previous agreements despite not being able to guarantee the land as 100% clear, while the Nation simply wanted the land cleared of all dangers.

Representatives of the Nation denied later suggestions by Military personnel that the disagreement was over money, with Chief Roy Whitney stating that “The point we’re trying to make is that our people are going to get hurt here if we don’t do something now.” Before long, an unfortunate reminder of the dangers associated with unexploded ordnances would serve to underscore the band’s grievances.

Just a week after the Tsuu T’ina blockade began, three soldiers at Canadian Forces Base Suffield hit an unexploded ordnance while digging a trench. All three soldiers required their legs to be amputated below the knee due to injuries sustained in the blast. The incident, as well as another non-injury incident at the Sarcee artillery range in 1987 where a solider also hit live shells with a shovel, was held as an example by the Nation of the potential dangers still prevalent on the Tsuu T’ina reserve.

The three-month blockade of the bridge succeeded in opening direct talks with Defence Minister Bill McKnight, and by September of 1989 the Nation and the DND had come to a preliminary agreement, at which point the blockade was removed. The Military had agreed to the continued clearing of the land in question to a higher standard than perviously agreed to, and both parties were amicable about the settlement. Normal usage of the land resumed, though even this was soon to change due to circumstances out of the control of either the Tsuu T’ina or the Military.

Wolf`s Flat Ordnance Disposal

The agreement that followed the blockade was finalized in March of 1990, and to start the process the Military contracted a portion of the clean up efforts to an American company, reportedly citing the lack of Canadians with the experience to do the job. The agreement also called for the Nation to be offered the opportunity to carry out some of the disposal work, at which point Chief Roy Whitney began to consider the formation of a Tsuu T’ina-owned and operated ordnance disposal company. Enlisting the expertise of an American Army ordnance disposal expert to train Nation members, by 1991 the Nation had established Wolf’s Flat Ordnance Disposal (The widely reported inception date of 1986 for the company seems not to be accurate). The company soon received the contract for ordnance disposal on the 3,800 acres of the former artillery range, and the first two months of clearing the artillery range reportedly yielded around one tonne of munitions, including at least 17 live ordnances.

In a 2000 interview, ordnance disposal consultant Captain Lloyd stated that in the time since the military initially cleared the land in 1981 “we have pulled out one million items of ordnance, expended rounds, live rounds”, the oldest of which reportedly dated to 1896. At the height of the clean-up, it was stated that 10 tonnes of old munitions were being collected annually. The numbers alone validated the concerns of the Tsuu T’ina, proving to them that the initial clearance efforts were not satisfactory.

By the mid 1990s, Wolf’s Flat Ordnance Disposal had expanded their operations beyond the Tsuu T’ina reserve and were soon consulting for other First Nations whose reserves had been used for military training, as well as winning clearance contracts in Panama, Kosovo and Nicaragua. Though the company is largely inactive now, the reserve is still home to many former employees of the company that are qualified in ordnance disposal.

Return of the Harvey Barracks

The lawsuit filed by the Nation in 1982 was only partially resolved under the 1985 lease agreement; the portion of the lawsuit related to the artillery range was settled, but the portion regarding the return of the barracks lands was still active in the early 1990s. Following continued pressure by the Nation and other external factors, an out-of-court settlement was reached in 1991. The Military had agreed to return the Harvey Barracks land to the Tsuu T’ina, though a series of leases were instituted that would allow the Military to continue to use portions of the barracks lands until the year 2050. The 1991 agreement also required all of the lands to be remediated to a standard suitable for residential use when vacated.

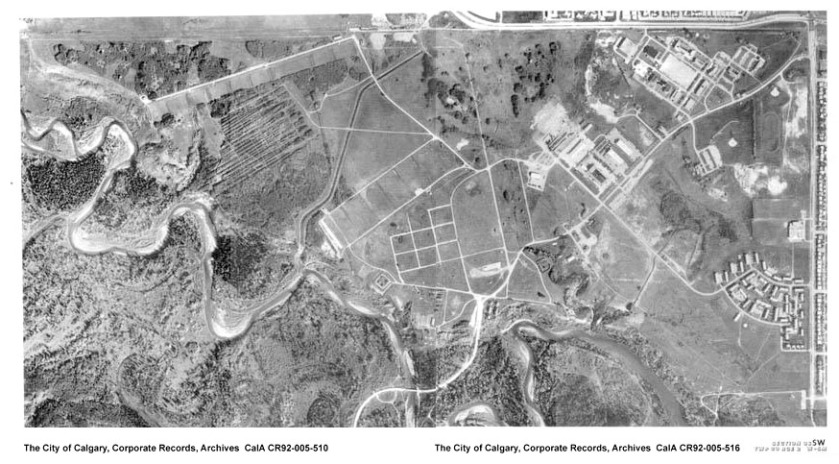

(The Harvey Barracks shown approximately 1973. Image composite of CalA CR92-005-510 and CalA CR92-005-516 courtesy of The City of Calgary, Corporate Records, Archives)

In early 1994 the Canadian government announced their decision to close the Harvey Barracks, and later decisions would see the entire Canadian Forces Base Calgary to closed. The closure of the Harvey Barracks was completed in 1996 and ordnance clearance efforts were soon initiated on the land, in addition to the clearance already underway on the artillery range. In accordance with the 1985 and 1991 agreements, the Military would continue to lease the land until it had been cleared and rehabilitated to a state suitable for residential use.

According to the Department of National Defence, the most recent clearance of the artillery range was initiated in 1988 and was set for completion in 2005. The Harvey Barracks land clearance reportedly lasted from 1998 to 2004 while the final element of the clearance, that of remediating the Elbow river, was undertaken between 2001 and 2006. In 2006 the Military formally returned the land to the Tsuu T’ina, having been certified as suitable for residential use by Golder Associates, an independent consultant who oversaw the clearance efforts on the Harvey Barracks portion of the land. Upon the return, Director of Environmental Engineering Management for the Department of National Defence Daniel Godbout stated that the return of the land was the result of 15 years of clearance that cost the government a total of over $130 million (though this figure conflicts somewhat with the $73 million figure quoted by the Department of National Defence only two years earlier in 2004).

The former Harvey Barracks land today is home to the Grey Eagle Casino, and plans have been drawn up for future development of most of this land. Click here for more information on the casino and it’s recent expansions, and of future development plans for the former barracks area.

UXO and the Ring Road

The lingering issue of unexploded ordnances also plays a role in the ring road story.

The 2009 plans for the ring road would have seen the road traverse the former Harvey Barracks and artillery range, and the construction of the road and interchanges would necessitate digging in lands once used for military training. In the years following the signing of the Framework Agreement with the Tsuu T’ina Nation in 2005, the Province engaged several companies to begin to assess the risk of unexploded ordnances along the ring road route. Consulting engineering firm Amec was hired to assist the Department of National Defence by creating a risk management framework, and was informed by information gathered from historic land-clearance data and a ‘targeted field investigation program’. Airborne geophysical surveys along the ring road route were also undertaken to assess the risks posed by unexploded ordnance.

In addition, the 2009 ring road plans included a proposal to realign the Elbow River in exactly the spot where ordnances were found in 2013 following the June floods. The 2009 agreement for the ring road contained language acknowledging the unexploded ordnance issue, and would have seen the federal government indemnifying the Province over any potential incidents.

Click for more information about the 2009 southwest ring road plans, and the 2009 ring road agreement.

A Lasting Legacy

Despite the intensive and costly efforts by the Military and the Tsuu T’ina to clear the former training lands, the recent re-surfacing of multiple shells has shown that the area is not entirely free of old munitions.

In July of 2013, following the flooding of southern Alberta, two unexploded ordnances were spotted on the banks of the Elbow river in the Weaselhead area within the City of Calgary. Discovered two weeks apart by different hikers in the area, the munitions were brought to the attention of the Calgary Police, who detonated them where they were found. The detonation of the first shell was carried out while the as-yet-undiscovered second shell lay less than 10 metres away, and while the second shell was not disturbed by the initial detonation, the incident served to highlight the lingering danger of unexploded ordnance in the area and of the importance of proper clearance and disposal.

Calgary Police Duty Inspector Darrell Hess is quoted saying “We’ve recovered (unexploded ordnance) before. Once or twice a year we get a call of someone locating or discovering some type of military ordinance that dates as far back as World War 2… Most of them are inert”. Indeed, the discovery of these unexploded ordnances was preceded in 2010 by another similar incident. In August of 2010 a man who was ‘geo-caching’ in southwest Calgary discovered an old shell at the edge of the Glenmore Reservoir near the Weaselhead. The Police determined that the shell did not need require detonation, but it’s location at the reservoir raised some concerns.

Natural events like frost-heave and flooding has been noted by the Canadian Military to be able to uncover unexploded ordnances from places that had previously been cleared for munitions, or to move them to areas that had never been exposed to live-fire training in the first place. As the use of live explosives was not reported to have occurred in the Reservoir area, it is likely that the ordnances found in 2010 and 2013 were naturally moved from practice ranges further upstream. In 2010, the City requested a review and assessment of maintenance work to be undertaken in the Weaselhead, and in response the Department of National Defence’s Unexploded Ordnance Legacy Sites Program conducted a survey and limited clearance efforts along the Elbow river that adjoined the barracks and artillery lands. No evidence of ordnance was found as a result of these efforts, and the risk of UXOs in the area was declared to be low.

Following the flooding of 2013 and the discovery of the two UXOs, the Weaselhead park was closed by the City of Calgary in order for the Department of National Defence to assess the park for further risk. The issue was further complicated by the presence of a high-pressure natural gas line that crosses the Elbow river in the Weaselhead area, and which was exposed in the floods.

Final Thoughts

Though the unexploded ordnance issue may stem from an old problem, the impacts are still being felt today. Areas long considered cleared can still yield unexpected dangers, and even areas that had never seen live fire can be affected.

In the Canadian Government’s own words “Many people think that UXO (unexploded ordnances) are not dangerous because they have been there for many decades. In fact, an UXO can become more unstable and more dangerous over time. Simply touching or moving it could cause it to explode. UXO can also move or be exposed over time. For example, freeze-thaw cycles, flooding and storms can uncover buried ordnance or move it from place to place. Just because no one has seen UXO in an area for many decades does not mean that it isn’t there now.”

—–

For more information about the Military’s use of Tsuu T’ina lands, see the excellent book ‘Battle Grounds‘ by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. For a look at unexploded ordnance clearance efforts around the world, The Canadian Film Board documentary ‘Aftermath: The Remnants of War’ is available to watch in it’s entirety here.

With thanks to Michael Nunn of the Calgary Police Service, Glennda Leslie at the City of Calgary Archives, Robert Dickinson at the City of Calgary and Mark Langenbacher.

Excellent article that is pertinent to Calgary residents, whether on the reserve or off, and a warning that articles of war, sadly, are ever present in our lives.

You mentioned a great source of info by Laukenbauer entitled ” Battlegrounds”. Do you have also a bibliography of your other sources of info. I’m trying to expand the Tsuu T’ina nation Wikipedia article. And although your blog is a GREAT source of info, both sided, and very non personalized (academic). Everything a good wikipedia article should be. Sadly it’s a blog and it’ll be rejected by more aggressive editors. Wikipedia seems to be a breeding ground for personal ego battles of intellectual masturbation for some editors. Their hunting grounds. (I’d use the scaterlogical territorial boundary term, but you get the idea). They would reject your writing. Unless it’s in “Book” format. Even though might I add your detailed research would be perfect sources… Again, it brings both sides of the issue for journalistic credibility. I have encountered an article written by Lauckenbauer in the wake of the 1998 “squatters” of Black bear crossing complex.. He also goes into detail of the events that led up to that, such as the lack of housing on the nation, and the need for the Grey Eagle.

I will be conducting a FOIP search on the water Master Plan shortly, now that I have free time. and would like to file my findings to you.

But if you don’t mind me asking. Where did you find such a wealth of information? Normally anything beyong 1990’s has not been cataloged in the databases, and or deleted as there is just too much information. You have photos of old mayors, old land lease agreements, maps, and everything comprehensive. Where did you find all this information? You shoud look at getting government funding for this blog as it’s really a good archive of old scraps of data for decades! An important piece of our history.

Thank you for the comments. When I set out to research and write about the history of the SW Ring Road (and later, the history of many more threads that tie into that narrative) I wanted to be as honest, accurate and unbiased as possible. For me, that meant getting original sources wherever possible.

Much of my research will start with one of the newspaper archives, but I will usually get documents from governmental archives to get the details right. My info comes from the City of Calgary archive, the Provincial archive, different federal archives (including the Privy Council, the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, Department of Natural Resources etc.) as well as by writing to different Federal/Provincial/Civic departments to see if they have documents that might be relevant. Also, speaking with current and previous players in this story has allowed me to fill in some of the previously unrecorded history of this project.

Everything in the blog is painstakingly researched, and I have copies of all of the sources for the claims in my writing. If I ever turn my blog into a book, I will of course include the sources. I totally understand why editors might be hesitant to reference my blog as a source. Saying that, I want people to trust my blog, and I am always willing to share sources if anyone writes to ask about a specific claim. Maybe when I have some time I can go back and add footnotes to my previous articles.

Great article. As someone intimately involved in the range clearance operations in the late 1990’s and a “born in sw Calgary ” resident I found this a fairly good article on the tsu Tina / Sarcee range history.

My Dad grew up on the Barracks (in the early 70s) and he would tell me about how it used to be a Range, but I never knew just how much Ordnance was actually used. I guess I’m quite lucky that my dad wasn’t one of those kids who found a UXO, or I might not be here today. I actually remember when they closed The Weaselhead after the flood, I was coming back from a bike around the Reservoir and not having any idea what was going. I had no clue there was that amount of UXO in my own backyard. Anyway, good read, very informative.